EDGAR ALLAN POE - Part 16

His chief intellectual development in this time was his new turn for analysis and detection. In May, 1841, he published in another magazine of Graham's a construction, from the first chapters which had recently appeared, of the plot of Barnaby Rudge. Dickens is said to have asked if Poe was the devil. He was devilish only in knowing how other men's minds must work under given conditions; and the conjuror's tricks of another plot-maker did not baffle him. He himself delighted to explain care fully how the conjuror performs, and after the explanation to startle the audience more than ever. He was busy about this time with his challenge to the world to send him cryptograms which he could not solve. He mastered all that came, and there is a curious implication in the terms of his challenge that any one who can use his brain can de cipher a cryptogram that any other brain can conceive, but that there is no one in the world but Poe who can use his brain. In this he was relatively right. Poe inevitably discovered that, compared with his own, the mental processes of humanity are feeble operations, and he loved to set the silly mouth of the world agape. But he laid up bitterness for himself in the unavoidable reflection that simpletons and dullards get on very well in the world, that they like each other and prosper, while he of the superior brain is marked for unsuccess and galling friction with the sluggard processes of common life.

His work as puzzle editor was tiring, and the records of it are of no literary value except to reveal Poe's inexhaustible brain power. In April appeared the first of his detective stories, "The Murders of the Rue Morgue," which fixed at the very inception of the form an ultimate standard of excellence. These detective stories are the emergence of Poe's intellect from confusing practical conditions. The man delighted to think, and in this period of comparative ease he indulged in the exercise of ratiocination. "The Murders of the Rue Morgue" is connected in its physical horror with his other weird tales 5 but in "The Purloined Letter" he came to the purest example of the tale of reason, for this, without sensational terror, holds the interest in the question how a mind thinks and how another mind should set to work to guess at the probable plottings of the first. "The Mystery of Marie Roget" is the boldest and most spectacular of the detective stories. In others, as Poe himself was the first to point out, the author invents both solution and problem, or follows a story of life which has been brought to conclusion. In "Marie Roget" Poe undertook to solve by thinly disguised parallel a murder plot which was being unfolded in contemporaneous newspapers, and which his conclusion forestalled in the ultimate development of the event.

Poe seems to have tried all the directions which the detective story will take, except one which he was temperamentally unable to follow. In later writers the detective story has merged with the novel of human life, in which our interests are engaged by other things than the sheer process of detection. To take a current example, the world can find human interest in the death and the love affairs and the pallid addiction to cocaine of Mr. Sherlock Holmes. Poe's persons, out of plot, are out of mind.

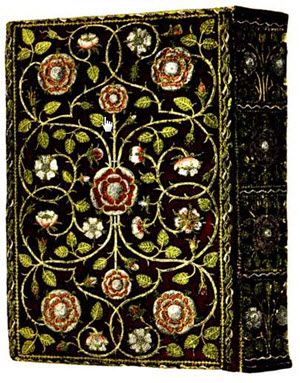

Poe added to his tales of horror "The Pit and the Pendulum" and "The Black Cat," and in "The Masque of the Bed Death" revealed his luxurious sense of color. This sense in his crude age and surroundings was easily perverted to a kind of riot in plush and tinsel magnificence which shows not so much his lack of taste as the yearnings of an impoverished man for warmth and splendour. He also wrote for Graham's some of his soundest criticisms, on Hawthorne, Longfellow, Dickens, Bulwer, Goldsmith, John Wilson, Macaulay, Lever, Marryat.