EDGAR ALLAN POE - Part 15

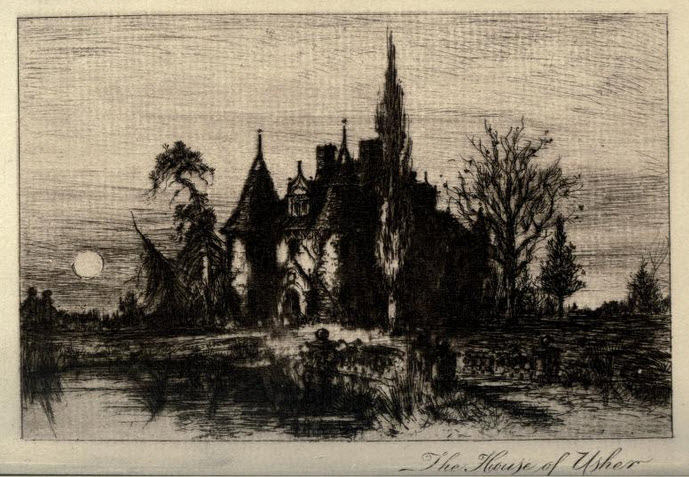

Fall of the House of Usher

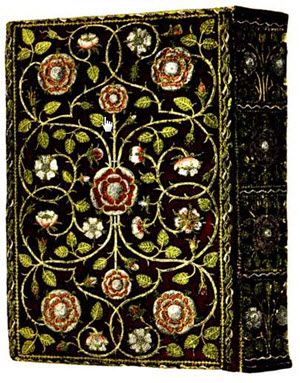

In 1839 he became contributor to Burton* s Gentleman's Magazine, published in Philadelphia, and in July was announced as associate editor. His contributions to this magazine gave it prosperity, and so increased his reputation that the hitherto doubtful publishers ventured to print the best book of short stories that America had produced. Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque appeared in two volumes at the end of 1839 or the beginning of 1840. These volumes contain several of Poe's master pieces,- " The Fall of the House of Usher," " William Wilson," " Shadow, > > "Silence," and "Ligeia." As Poe matured, his tales of horror became less physical, more intellectual, and dealt with the mysteries of conscience, will, life after death. He had a superstitious rather than a scientific interest in the shadowy problems of psychology, metempsychosis, the nature of personality, hypnotism, and the rest. In this he is like Hawthorne. One difference is that Poe fetches the shadows out into the open analysis of his brilliant, confident style, whereas Hawthorne leaves them dim, soft, in the distances of religious and poetic wonder. Moreover, the specters in whom Hawthorne embodies mesmeric suggestions, his victims of con science, the spooks that appear and disappear amid allegorical portents, now and again step forward and speak with human voices. Poe never contrived a human being: the conversations of his characters are but the vehicles of expository ideas. Compared to the dramatically real double person, Jekyll-Hyde, William Wilson is a ghost. "Morella," "Berenice," "Ligeia," are but the transparent images of revery laid against the plane surface of a mathematical plan. When Poe reached out for a human being, one who might come ready-made from the byways of life into the particular course he was laying out for his story, he pressed human truth out of the figure after a minute of handling

Foe's association with Burton lasted until the summer of 1840, when Foe announced the magazine which he always hoped to found and never did. perhaps Burton objected to a plan that meant a loss to the Gentleman's Magazine, and it may be that Poe, in new hope of in dependence, became a troublesome employee and made improper use of Bur ton's subscription lists. Burton circulated abusive reports of Poe's habits, but wished for business reasons to get him back on the magazine. Poe called Bur ton a scoundrel, and Poe's scoundrels were often persons he had offended. When in 1841 Graham took the Gentle man's Magazine over, Burton stipulated that his young editor was to be taken care of.

In the magazine for June appeared the last instalment of "The Journal of Julius Bodman," in which Poe tried to do with land adventure what he had done with sea adventure in the story of Pym. It was never brought to completion on account of Poe's break with the magazine ; but it is interesting in that it was not remembered as Poe's work until in 1880 the English biographer, Ingram, discovered it in the files of Butori's, and it illustrates the curious Elizabethan vagabondage of Poe 7 s writings, unusual in modern literature. No further work of his is identified until the December number, in which appeared "The Man of the Crowd, 77 a parable of conscience. Poe abandoned for the time his plan for a magazine of his own, and entered upon a period of relatively prosperous writing and editing for the mag azine which George Graham made out of Burton's and another. He found time for contributions to other magazines, and was for two years industrious and fairly well off under the friendly Graham.