THE MAN OF THE CROWD.

by Edgar Allan PoeCe grand malheur, de ne pouvoir être seul.

La Bruyère.

IT was well said of a certain German book that "er lasst sich nicht

lesen" - it does not permit itself to be read. There are some secrets

which do not permit themselves to be told. Men die nightly in their beds,

wringing the hands of ghostly confessors and looking them piteously in the

eyes -- die with despair of heart and convulsion of throat, on account of

the hideousness of mysteries which will not suffer themselves to be

revealed. Now and then, alas, the conscience of man takes up a burthen so

heavy in horror that it can be thrown down only into the grave. And thus

the essence of all crime is undivulged.

Not long ago, about the closing in of an evening in autumn, I sat at

the large bow window of the D---- Coffee-House in London. For some months

I had been ill in health, but was now convalescent, and, with returning

strength, found myself in one of those happy moods which are so precisely

the converse of ennui - moods of the keenest appetency, when the film from

the mental vision departs - the "PL> 0 BDT ,B,L - and the intellect,

electrified, surpasses as greatly its every-day condition, as does the

vivid yet candid reason of Leibnitz, the mad and flimsy rhetoric of

Gorgias. Merely to breathe was enjoyment; and I derived positive pleasure

even from many of the legitimate sources of pain. I felt a calm but

inquisitive interest in every thing. With a cigar in my mouth and a

newspaper in my lap, I had been amusing myself for the greater part of the

afternoon, now in poring over advertisements, now in observing the

promiscuous company in the room, and now in peering through the smoky

panes into the street.

This latter is one of the principal thoroughfares of the city, and had

been very much crowded during the whole day. But, as the darkness came on,

the throng momently increased; and, by the time the lamps were well

lighted, two dense and continuous tides of population were rushing past

the door. At this particular period of the evening I had never before been

in a similar situation, and the tumultuous sea of human heads filled me,

therefore, with a delicious novelty of emotion. I gave up, at length, all

care of things within the hotel, and became absorbed in contemplation of

the scene without.

At first my observations took an abstract and generalizing turn. I looked

at the passengers in masses, and thought of them in their aggregate

relations. Soon, however, I descended to details, and regarded with minute

interest the innumerable varieties of figure, dress, air, gait, visage,

and expression of countenance.

By far the greater number of those who went by had a satisfied

business-like demeanor, and seemed to be thinking only of making their way

through the press. Their brows were knit, and their eyes rolled quickly;

when pushed against by fellow-wayfarers they evinced no symptom of

impatience, but adjusted their clothes and hurried on. Others, still a

numerous class, were restless in their movements, had flushed faces, and

talked and gesticulated to themselves, as if feeling in solitude on

account of the very denseness of the company around. When impeded in their

progress, these people suddenly ceased muttering, but re-doubled their

gesticulations, and awaited, with an absent and overdone smile upon the

lips, the course of the persons impeding them. If jostled, they bowed

profusely to the jostlers, and appeared overwhelmed with confusion. -

There was nothing very distinctive about these two large classes beyond

what I have noted. Their habiliments belonged to that order which is

pointedly termed the decent. They were undoubtedly noblemen, merchants,

attorneys, tradesmen, stock-jobbers - the Eupatrids and the common-places

of society - men of leisure and men actively engaged in affairs of their

own - conducting business upon their own responsibility. They did not

greatly excite my attention.

The tribe of clerks was an obvious one and here I discerned two remarkable

divisions. There were the junior clerks of flash houses - young gentlemen

with tight coats, bright boots, well-oiled hair, and supercilious lips.

Setting aside a certain dapperness of carriage, which may be termed

deskism for want of a better word, the manner of these persons seemed to

me an exact fac-simile of what had been the perfection of bon ton about

twelve or eighteen months before. They wore the cast-off graces of the

gentry; - and this, I believe, involves the best definition of the class.

The division of the upper clerks of staunch firms, or of the "steady old

fellows," it was not possible to mistake. These were known by their coats

and pantaloons of black or brown, made to sit comfortably, with white

cravats and waistcoats, broad solid-looking shoes, and thick hose or

gaiters. - They had all slightly bald heads, from which the right ears,

long used to pen-holding, had an odd habit of standing off on end. I

observed that they always removed or settled their hats with both hands,

and wore watches, with short gold chains of a substantial and ancient

pattern. Theirs was the affectation of respectability; - if indeed there

be an affectation so honorable.

There were many individuals of dashing appearance, whom I easily

understood as belonging to the race of swell pick-pockets with which all

great cities are infested. I watched these gentry with much

inquisitiveness, and found it difficult to imagine how they should ever be

mistaken for gentlemen by gentlemen themselves. Their voluminousness of

wristband, with an air of excessive frankness, should betray them at once.

The gamblers, of whom I descried not a few, were still more easily

recognisable. They wore every variety of dress, from that of the desperate

thimble-rig bully, with velvet waistcoat, fancy neckerchief, gilt chains,

and filagreed buttons, to that of the scrupulously inornate clergyman,

than which nothing could be less liable to suspicion. Still all were

distinguished by a certain sodden swarthiness of complexion, a filmy

dimness of eye, and pallor and compression of lip. There were two other

traits, moreover, by which I could always detect them; - a guarded lowness

of tone in conversation, and a more than ordinary extension of the thumb

in a direction at right angles with the fingers. - Very often, in company

with these sharpers, I observed an order of men somewhat different in

habits, but still birds of a kindred feather. They may be defined as the

gentlemen who live by their wits. They seem to prey upon the public in two

battalions - that of the dandies and that of the military men. Of the

first grade the leading features are long locks and smiles; of the second

frogged coats and frowns.

Descending in the scale of what is termed gentility, I found darker and

deeper themes for speculation. I saw Jew pedlars, with hawk eyes flashing

from countenances whose every other feature wore only an expression of

abject humility; sturdy professional street beggars scowling upon

mendicants of a better stamp, whom despair alone had driven forth into the

night for charity; feeble and ghastly invalids, upon whom death had placed

a sure hand, and who sidled and tottered through the mob, looking every

one beseechingly in the face, as if in search of some chance consolation,

some lost hope; modest young girls returning from long and late labor to a

cheerless home, and shrinking more tearfully than indignantly from the

glances of ruffians, whose direct contact, even, could not be avoided;

women of the town of all kinds and of all ages - the unequivocal beauty in

the prime of her womanhood, putting one in mind of the statue in Lucian,

with the surface of Parian marble, and the interior filled with filth -

the loathsome and utterly lost leper in rags - the wrinkled, bejewelled

and paint-begrimed beldame, making a last effort at youth - the mere child

of immature form, yet, from long association, an adept in the dreadful

coquetries of her trade, and burning with a rabid ambition to be ranked

the equal of her elders in vice; drunkards innumerable and indescribable -

some in shreds and patches, reeling, inarticulate, with bruised visage and

lack-lustre eyes - some in whole although filthy garments, with a slightly

unsteady swagger, thick sensual lips, and hearty-looking rubicund faces -

others clothed in materials which had once been good, and which even now

were scrupulously well brushed - men who walked with a more than naturally

firm and springy step, but whose countenances were fearfully pale, whose

eyes hideously wild and red, and who clutched with quivering fingers, as

they strode through the crowd, at every object which came within their

reach; beside these, pie-men, porters, coal- heavers, sweeps;

organ-grinders, monkey-exhibiters and ballad mongers, those who vended

with those who sang; ragged artizans and exhausted laborers of every

description, and all full of a noisy and inordinate vivacity which jarred

discordantly upon the ear, and gave an aching sensation to the eye.

As the night deepened, so deepened to me the interest of the scene; for

not only did the general character of the crowd materially alter (its

gentler features retiring in the gradual withdrawal of the more orderly

portion of the people, and its harsher ones coming out into bolder relief,

as the late hour brought forth every species of infamy from its den,) but

the rays of the gas-lamps, feeble at first in their struggle with the

dying day, had now at length gained ascendancy, and threw over every thing

a fitful and garish lustre. All was dark yet splendid - as that ebony to

which has been likened the style of Tertullian.

The wild effects of the light enchained me to an examination of individual

faces; and although the rapidity with which the world of light flitted

before the window, prevented me from casting more than a glance upon each

visage, still it seemed that, in my then peculiar mental state, I could

frequently read, even in that brief interval of a glance, the history of

long years.

With my brow to the glass, I was thus occupied in scrutinizing the mob,

when suddenly there came into view a countenance (that of a decrepid old

man, some sixty-five or seventy years of age,) - a countenance which at

once arrested and absorbed my whole attention, on account of the absolute

idiosyncrasy of its expression. Any thing even remotely resembling that

expression I had never seen before. I well remember that my first thought,

upon beholding it, was that Retzch, had he viewed it, would have greatly

preferred it to his own pictural incarnations of the fiend. As I

endeavored, during the brief minute of my original survey, to form some

analysis of the meaning conveyed, there arose confusedly and paradoxically

within my mind, the ideas of vast mental power, of caution, of

penuriousness, of avarice, of coolness, of malice, of blood thirstiness,

of triumph, of merriment, of excessive terror, of intense - of supreme

despair. I felt singularly aroused, startled, fascinated. "How wild a

history," I said to myself, "is written within that bosom!" Then came a

craving desire to keep the man in view - to know more of him. Hurriedly

putting on an overcoat, and seizing my hat and cane, I made my way into

the street, and pushed through the crowd in the direction which I had seen

him take; for he had already disappeared. With some little difficulty I at

length came within sight of him, approached, and followed him closely, yet

cautiously, so as not to attract his attention.

I had now a good opportunity of examining his person. He was short in

stature, very thin, and apparently very feeble. His clothes, generally,

were filthy and ragged; but as he came, now and then, within the strong

glare of a lamp, I perceived that his linen, although dirty, was of

beautiful texture; and my vision deceived me, or, through a rent in a

closely-buttoned and evidently second-handed roquelaire which enveloped

him, I caught a glimpse both of a diamond and of a dagger. These

observations heightened my curiosity, and I resolved to follow the

stranger whithersoever he should go.

It was now fully night-fall, and a thick humid fog hung over the city,

soon ending in a settled and heavy rain. This change of weather had an odd

effect upon the crowd, the whole of which was at once put into new

commotion, and overshadowed by a world of umbrellas. The waver, the

jostle, and the hum increased in a tenfold degree. For my own part I did

not much regard the rain - the lurking of an old fever in my system

rendering the moisture somewhat too dangerously pleasant. Tying a

handkerchief about my mouth, I kept on. For half an hour the old man held

his way with difficulty along the great thoroughfare; and I here walked

close at his elbow through fear of losing sight of him. Never once turning

his head to look back, he did not observe me. By and bye he passed into a

cross street, which, although densely filled with people, was not quite so

much thronged as the main one he had quitted. Here a change in his

demeanor became evident. He walked more slowly and with less object than

before - more hesitatingly. He crossed and re-crossed the way repeatedly

without apparent aim; and the press was still so thick that, at every such

movement, I was obliged to follow him closely. The street was a narrow and

long one, and his course lay within it for nearly an hour, during which

the passengers had gradually diminished to about that number which is

ordinarily seen at noon in Broadway near the Park - so vast a difference

is there between a London populace and that of the most frequented

American city. A second turn brought us into a square, brilliantly

lighted, and overflowing with life. The old manner of the stranger

re-appeared. His chin fell upon his breast, while his eyes rolled wildly

from under his knit brows, in every direction, upon those who hemmed him

in. He urged his way steadily and perseveringly. I was surprised, however,

to find, upon his having made the circuit of the square, that he turned

and retraced his steps. Still more was I astonished to see him repeat the

same walk several times -- once nearly detecting me as he came round with

a sudden movement.

In this exercise he spent another hour, at the end of which we met with

far less interruption from passengers than at first. The rain fell fast;

the air grew cool; and the people were retiring to their homes. With a

gesture of impatience, the wanderer passed into a bye-street comparatively

deserted. Down this, some quarter of a mile long, he rushed with an

activity I could not have dreamed of seeing in one so aged, and which put

me to much trouble in pursuit. A few minutes brought us to a large and

busy bazaar, with the localities of which the stranger appeared well

acquainted, and where his original demeanor again became apparent, as he

forced his way to and fro, without aim, among the host of buyers and

sellers.

During the hour and a half, or thereabouts, which we passed in this place,

it required much caution on my part to keep him within reach without

attracting his observation. Luckily I wore a pair of caoutchouc

over-shoes, and could move about in perfect silence. At no moment did he

see that I watched him. He entered shop after shop, priced nothing, spoke

no word, and looked at all objects with a wild and vacant stare. I was now

utterly amazed at his behavior, and firmly resolved that we should not

part until I had satisfied myself in some measure respecting him.

A loud-toned clock struck eleven, and the company were fast deserting the

bazaar. A shop-keeper, in putting up a shutter, jostled the old man, and

at the instant I saw a strong shudder come over his frame. He hurried into

the street, looked anxiously around him for an instant, and then ran with

incredible swiftness through many crooked and people-less lanes, until we

emerged once more upon the great thoroughfare whence we had started -- the

street of the D---- Hotel. It no longer wore, however, the same aspect. It

was still brilliant with gas; but the rain fell fiercely, and there were

few persons to be seen. The stranger grew pale. He walked moodily some

paces up the once populous avenue, then, with a heavy sigh, turned in the

direction of the river, and, plunging through a great variety of devious

ways, came out, at length, in view of one of the principal theatres. It

was about being closed, and the audience were thronging from the doors. I

saw the old man gasp as if for breath while he threw himself amid the

crowd; but I thought that the intense agony of his countenance had, in

some measure, abated. His head again fell upon his breast; he appeared as

I had seen him at first. I observed that he now took the course in which

had gone the greater number of the audience - but, upon the whole, I was

at a loss to comprehend the waywardness of his actions.

As he proceeded, the company grew more scattered, and his old uneasiness

and vacillation were resumed. For some time he followed closely a party of

some ten or twelve roisterers; but from this number one by one dropped

off, until three only remained together, in a narrow and gloomy lane

little frequented. The stranger paused, and, for a moment, seemed lost in

thought; then, with every mark of agitation, pursued rapidly a route which

brought us to the verge of the city, amid regions very different from

those we had hitherto traversed. It was the most noisome quarter of

London, where every thing wore the worst impress of the most deplorable

poverty, and of the most desperate crime. By the dim light of an

accidental lamp, tall, antique, worm-eaten, wooden tenements were seen

tottering to their fall, in directions so many and capricious that scarce

the semblance of a passage was discernible between them. The paving-stones

lay at random, displaced from their beds by the rankly-growing grass.

Horrible filth festered in the dammed-up gutters. The whole atmosphere

teemed with desolation. Yet, as we proceeded, the sounds of human life

revived by sure degrees, and at length large bands of the most abandoned

of a London populace were seen reeling to and fro. The spirits of the old

man again flickered up, as a lamp which is near its death hour. Once more

he strode onward with elastic tread. Suddenly a corner was turned, a blaze

of light burst upon our sight, and we stood before one of the huge

suburban temples of Intemperance - one of the palaces of the fiend, Gin.

It was now nearly day-break; but a number of wretched inebriates still

pressed in and out of the flaunting entrance. With a half shriek of joy

the old man forced a passage within, resumed at once his original bearing,

and stalked backward and forward, without apparent object, among the

throng. He had not been thus long occupied, however, before a rush to the

doors gave token that the host was closing them for the night. It was

something even more intense than despair that I then observed upon the

countenance of the singular being whom I had watched so pertinaciously.

Yet he did not hesitate in his career, but, with a mad energy, retraced

his steps at once, to the heart of the mighty London. Long and swiftly he

fled, while I followed him in the wildest amazement, resolute not to

abandon a scrutiny in which I now felt an interest all-absorbing. The sun

arose while we proceeded, and, when we had once again reached that most

thronged mart of the populous town, the street of the D---- Hotel, it

presented an appearance of human bustle and activity scarcely inferior to

what I had seen on the evening before. And here, long, amid the momently

increasing confusion, did I persist in my pursuit of the stranger. But, as

usual, he walked to and fro, and during the day did not pass from out the

turmoil of that street. And, as the shades of the second evening came on,

I grew wearied unto death, and, stopping fully in front of the wanderer,

gazed at him steadfastly in the face. He noticed me not, but resumed his

solemn walk, while I, ceasing to follow, remained absorbed in

contemplation. "This old man," I said at length, "is the type and the

genius of deep crime. He refuses to be alone. [page 228:] He is the man of

the crowd. It will be in vain to follow; for I shall learn no more of him,

nor of his deeds. The worst heart of the world is a grosser book than the

'Hortulus Animæ,' {*1} and perhaps it is but one of the great mercies of

God that 'er lasst sich nicht lesen.' "

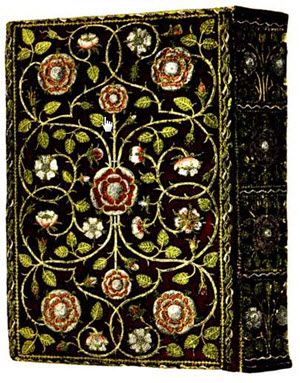

{*1} The "Hortulus Animæ cum Oratiunculis Aliquibus Superadditis" of

Grünninger

2021

Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe Online: Poems of Edgar Allan Poe | Works of Edgar Allan Poe - volume 1 | Works of Edgar Allan Poe - volume 2 | Works of Edgar Allan Poe - volume 3 | Works of Edgar Allan Poe - volume 4 | Works of Edgar Allan Poe - volume 5 |